This week we have an amazing blog piece by Rachel Piso, who has dug deep into the history of samplers in the past, but now looks into something not that many people are willing to talk about; mourning samplers.

In my last post about historical cross stitch, in which I listed the reasons I’m so in love with samplers, I talked about the aspects of the stitchers’ lives that were recorded in fabric—namely their education, status, families, and interests. Going deeper, I’ve been reading about how all of those qualities represented their feelings, roles, and experiences surrounding death.

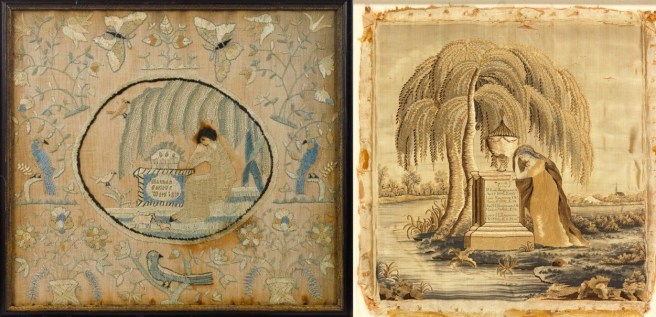

I’ve admired mourning samplers for as long as I’ve been studying antique needlework, although I never really got far beyond their beauty and technique. Most of them held similar imagery: a grieving woman draped over a tomb surrounded by willow trees. After reading further, I realized how this visual was representative of women and their roles at the time, especially relating to pain and misery.

In the 18th century, death had been moved from homes to hospitals and therefore made more private and personal. It became “fashionable” to mourn. This led right into the Victorian era when an entire etiquette formed around mourning (e.g. the heavy black dresses, veils, armbands, etc.).

It was accepted that men were stoic and self-controlled, while women were sentimental and over-emotional. Melancholy was a distinctly feminine trait, even considered an illness (see also: female hysteria, but that’s a whole other subject I’m also fascinated with). You can see these gender roles represented in the samplers.

With the culture shift to intense displays of grief, and since needlework was already an established component of girls’ education, mourning samplers became popular.

While it seems that these pieces were completed with the idea of working through loss, the fancier samplers (called “fancywork,” appropriately) were assigned as school projects and as a way of demonstrating skill, especially for the upper-class. And not only were they used as teaching tools for advanced cross stitch and embroidery, but they also instilled society’s expectations of a proper girl: to keep busy, be patient, and have good taste and morals. They were proudly displayed in homes as an example of the accomplishment and character of the girl who created them. All in all, they were evidence of the abilities that would make her a desirable wife.

Of course, they were also works of art used to remember a loved one in a time before photography. Some even included “hair work”—stitches made with the hair of the person who had died. Side note: I’ve tried this with my own hair. Not easy.

There is so much to learn and examine with mourning samplers that I could write about them for weeks, but as usual, I was overly-excited about some antiques I found and needed to talk about them. This is very bare-bones info on the subject, but I hope to touch on them more in the future.

Note: If you’re interested in learning more, many books centered around cross stitch history touch on them. I also recommend Women and the Material Culture of Death (edited by Maureen Daly Goggin and Beth Fowkes Tobin) which examines the things women create/wear/keep in connection with death and mourning.

Originally posted on Rachel Piso’s blog.